The design phase of the product lifecycle: Why it's important and how Suqaba helps

Our previous post introduced Suqaba — what it is, what we do, and how it differs from the conventional engineering simulation tools that have dominated the industry for decades. To briefly recap: Suqaba is the first simulation platform to bring automated error verification directly into the engineering design process. By quantifying simulation error, Suqaba allows engineers to measure how closely a simulation prediction represents the real-world physics it intends to represent. In doing so, we provide a quantified measure of confidence — not just that a design works in theory, but that it will behave as expected once it leaves the screen and enters the physical world. This quantified approach to verification translates directly into fewer errors, fewer reworks, fewer costs, and importantly for today's blog post — can massively help reduce product design lifecycle times.

Today we will focus on the product design lifecycle. Why? Because to understand Suqaba's impact, we need to look at where simulation fits into the product lifecycle — and how the design phase determines the success or failure of everything that follows.

Just as a living being experiences all the stages from birth to death, a product undergoes its own life cycle from conception to market withdrawal. In broad terms, this lifecycle includes ideation, design, testing, production, market release, and finally decommissioning or replacement.

Each of these stages comes with its own challenges. The design phase is when simulation and verification are leveraged. The part is modeled (virtually) and tested against various conditions to see how the structure could and would perform under different physical conditions. This essentially saves the time, resources and cost (human and material) that would be spent on actually building the part or structure and performing physical experiments. So, if you want to test how well the handle of a plane door withstands different mechanical stressors, you don't have to wait until the handle is built, attached onto a door and the stressors are tested, to see how your structure holds up. Of course, physical experiments do occur (and they must), but in the design phase you virtually test these conditions on your supposed structure.

The simulated design will then elaborate on the behavior of your modeled structure, based on which you can modify the design to optimize it. Thus, when the stage of experimenting with the actual live part arrives, it will be about dealing with unexpected challenges and fine-tuning impacts that your simulation/design phase had not been able to cover. It's efficient and effective, and early in the product lifecycle — before human and material energy, time and cost have been expended. The design phase defines critical downstream decisions — from how a part will be manufactured to how it will perform, be maintained, and eventually retired. So, decisions taken at this stage have ripple effects.

Why does this efficiency matter? In addition to saving resources and cost, as mentioned, it's also about time and speed. Today, manufacturing operates under unprecedented pressure. Increasing complexity of products, tighter budgets, shrinking timelines for product development and increased competition all mean that companies are looking to streamline their processes [1]. In the automotive industry, for example, time-to-markets have been halved in the last decade with development cycles now averaging around two years [2]. Aerospace products, which used to span 15-20 years from concept to launch, are now expected in roughly a decade. Meanwhile, production lines in manufacturing may turn over in a matter of months.

This accelerated pace means companies have to innovate faster while maintaining (or even improving) safety, quality, and performance. In safety-critical fields like aerospace or automotive manufacturing, this balancing is crucial — constantly striving towards optimization at various levels, but never at the expense of safety. And of course, we have recently seen the disastrous effects when this balance is lost — as with Boeing [3, 4]. Strong simulation programs can safely save time without compromising on safety.

So, emulating real-world conditions in a computer-generated simulation during the design phase works great at optimizing the product lifecycle. But there is a caveat here — this only works on the assumption that the simulation program works well, i.e., precise, accurate, and complete in its capabilities. And this is not possible when the simulation program does not offer quantified error verification — which happens to be the case with simulation programs on the market today and also happens to be what Suqaba innovates (more on this later in this post, but also refer to our first blog post for details on why Suqaba is state of the art).

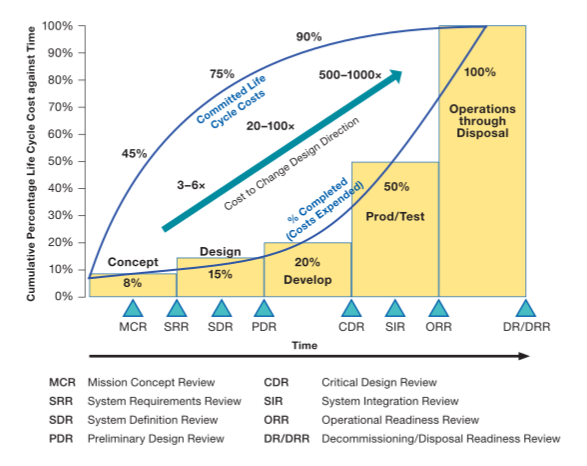

Without error verification, decisions taken at the design phase are based on guesswork. It relies heavily on the expertise of the user and the tribal knowledge they possess. This works if in the end it turns out the decision taken was the right one. If it isn't the right decision, however, it impacts phases further down in the cycle. Decisions made during the design phase determine up to 75% of the total lifecycle cost, even though the design phase itself represents only about 15% of total expenses (see chart below). Errors here mean failed prototypes, product recalls, or worse, safety incidents. There is also an exponential increase in costs over time when errors go undetected in this phase. For every dollar spent fixing an issue immediately in the design phase, a company could end up losing up to $1,000 if the error is ignored and must be corrected later downstream.

Impact of decisions made in the design phase on lifecycle cost (adapted from INCOSE-TP-2003-002-04, 2015).

As mentioned earlier, current simulation technology on the market does not offer quantified verification of model accuracy. In other words, a prediction of your modeled part's behavior under specified conditions is given but there is no measure of how much this prediction matches the physics being modeled — and ideally, the real-world behavior of a part must match what the physics theoretically states it must be. If it does, you know how your part is going to hold up under various stresses and strains. If it doesn't, then the behavior of your part becomes unpredictable and can lead to all the issues aforementioned — malfunctions, recalls, and other downstream effects on time and cost. To determine if the computed results are close to the physics being modeled (and how much so), engineers are then left to rely on expertise, experience, tribal knowledge, and manual hand-calculation. In essence, it is guesswork — calculated, experienced, educated guesswork, but guesswork, nonetheless.

By introducing automated error verification, Suqaba gives engineers a measurable accuracy rating for their simulations. It doesn't just show what the model predicts — it tells you how much you can trust those predictions. This bridges the gap between digital and physical, transforming simulation from a best guess into a verified design process. With this capability, Suqaba offers:

Confidence in simulation results grounded in quantified data

Fewer reworks and physical test failures

Reduced cognitive load and fatigue for engineers

Faster, safer, and more cost-efficient product development

Operational efficiency follows naturally from Suqaba's built-in error verification, serving as a powerful form of risk mitigation. In essence, Suqaba ensures that time saved in design doesn't come at the cost of quality, safety, or engineer well-being.

And this last point, the human cost, is a facet that is often overlooked. Manual meshing, having to rely on tribal knowledge and taking educated guesses on the accuracy of the model's predictions are not only inefficient on the workflow, but also produce enormous amounts of strain and fatigue on engineers and other technical staff that are often already overworked. In-house simulation has increasingly been integrated directly into the design workflow [5]. Rather than relying on a small group of simulation specialists — a common bottleneck in engineering organizations — design engineers themselves can simulate, iterate, and refine in real time. The Aberdeen Group's research reflects this shift: by 2016, 87% of best-in-class companies had incorporated simulation early in design, up from 75% just two years prior [5]. Moreover, 73% of these leaders verified product designs earlier in development through computational modeling, ensuring proof-of-concept validation well before physical testing [5]. Thus, while removing bottlenecks in workflow, it does add greater workload to the engineers in question.

This is then compounded by the fact that today's simulation tools are often tedious, manual, and time-consuming. Engineers spend countless hours on fine-tuning parameters, adjusting meshes, debugging models, and validating results. This heavy cognitive load leads to fatigue, decision errors, and inconsistent quality checks. In effect, the very tools designed to improve efficiency can end up slowing teams down and cause the build of cognitive fatigue and load. This in turn can lead to delays in workflow (at best), and errors in part production that can have serious and sometimes dangerous consequences. In some cases, it might even mean the total non-performance of quality checks.

But Suqaba, helps tackle that aspect too. In the end, it's a guarantee of model accuracy and workflow efficiency that will benefit all levels of a company.

To conclude, the design phase is paramount in the product lifecycle. It determines how efficiently a company can innovate, how quickly it can bring products to market, and how confidently it can stand behind what it builds. Simulation remains one of the most powerful tools in this process — but it is only as valuable as its accuracy and reliability. By embedding automated error verification directly into simulation workflows, Suqaba not only accelerates the design process but also elevates its integrity. It allows engineers to design with confidence, knowing their models align with the laws of physics.

In the end, reducing lifecycle time and cost is about speed and trust — in the tools, the results, and the people behind them. And that's precisely where Suqaba stands apart.

References

[1] Mourtzis, D. (2016). Challenges and future perspectives for the life cycle of manufacturing networks in the mass customisation era. Logistics Research, 9(1), 2.

[2] Sabadka, Dusan & Molnar, Vieroslav & Fedorko, Gabriel. (2019). Shortening of Life Cycle and Complexity Impact on the Automotive Industry. TEM Journal. 1295-1301. 10.18421/TEM84-27.

[3] https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/faa-continues-hold-boeing-accountable-implementing-safety-and-production-quality-fixes

[4] https://www.transportation.gov/faa-oversight-boeings-broken-safety-culture-0

[5] Cline, G. (2017). The benefits of simulation-driven design. Aberdeen Group: Waltham, MA, USA.